- Home

- Josh Chetwynd

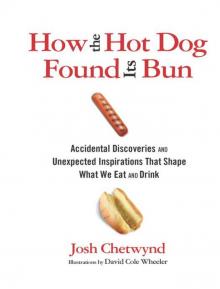

How the Hot Dog Found Its Bun Page 9

How the Hot Dog Found Its Bun Read online

Page 9

Shashikant Phadnis’s mistake, which led to Splenda, wasn’t a product of poor cleanliness. It was due to miscommunication. In 1975, the native of India was a student at Queen Elizabeth College in London working on an experiment with a highly toxic chemical called sulfuryl chloride. At one point in the proceedings, Phadnis’s adviser asked him to “test” his work. Maybe it was the professor’s British accent, but the student thought he said to “taste” his work. Despite the toxicity, the dutiful student followed orders. Panicked, the teacher asked if Phadnis was crazy. But fears soon turned to excitement when it turned out that the mixture’s toxicity had been neutralized and the result was a calorie-free powder 200 times sweeter than sugar.

Baking Powder: Adoring husband

Baking powder doesn’t seem like a building block for romance. But the invention of this product—which would become a fantastic yeast substitute for making bread, biscuits, and muffins—was essentially a love letter to a woman. The yearning man who channeled his feelings was Alfred Bird. A pharmacist from England’s Birmingham area, Bird set up his own shop in 1837 dispensing the usual elixirs and medicines.

The new business kept the twenty-four-year-old Bird busy, but the man had something more important to consider. He’d recently married and, unfortunately, his fair wife Elizabeth wasn’t the stoutest of individuals. Most notably, she suffered from digestive problems, making bread products nearly impossible to enjoy. That wouldn’t do for the newlywed Bird. He resolved to devise some way for his bride to enjoy scones and morning toast.

It didn’t happen overnight, but in 1843 Bird came up with a substance he called “Fermenting Powder.” Later renamed baking powder, the stuff did the trick. Not only could Elizabeth enjoy bread without tummy troubles, but the results were also lighter and fluffier than many traditional breads. Bird then matched his marital devotion with an impressive business sense. He invested heavily on marketing, giving away free calendars featuring ads for his powder. One of his favorite mottos was “Early to Bed, Early to Rise, Stick to Your Work and Advertise.”

Beyond the paying public, he was also able to convince Her Majesty’s armed forces that his invention would be perfect for baking fresh bread on military fronts and for hospital patients, whose diets might be limited by injury during the Crimean War. Bird would seal the deal with the Duke of Newcastle, who was the country’s prime minister at the time, by personally making five loaves to prove his product’s integrity.

His wife’s infirmity paid dividends with baking powder, but it wasn’t the only time Elizabeth’s maladies made Bird rich. Along with her inability to eat regular bread (problem solved), Mrs. Bird was also allergic to eggs. One dish she particularly longed for was custard. The loving Bird went to work again. He created a custard using corn flour instead of eggs as the basis. Easy to prepare and as tasty as the real thing, the new custard was wildly successful, especially in times of war when eggs were scarce.

Bird never stopped tinkering. He came up with an oil-powered lamp that could be refilled while still on and he liked to study storm patterns with the use of a huge barometer he hung in one of his stores. Neither of those were money makers like his powders, demonstrating nothing inspires like love for a good—albeit sickly—woman.

Corn Starch: Indomitable chemist

Admittedly, corn starch isn’t the sexiest entry in this book. For those readers who spend more time eating than cooking, it’s a valuable ingredient for thickening gravies, sauces, and puddings. While its purpose may yield a yawn, the story of its discovery is a compelling combination of perseverance and a dash of luck at just the right time.

Starches date back at least two thousand years. Their production is a painstaking process that requires a complicated combination of steps to extract the substance. In the early days, wheat and potatoes were primarily used in starch production. Yet, even then, only small amounts could be removed. It was such a costly endeavor that during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, there was a law that prevented the use of starch for any purpose other than to style wigs and stiffen the ruffles worn by the queen and her court. Over time innovations in the manufacturing process increased production enough for other everyday uses.

In the 1830s Thomas Kingsford was aware of the labor-intensive process required to make starches. A British native, Kingsford had immigrated to the United States to seek his fortune. While in England he’d worked as both a baker and at a chemical factory, and when he arrived in America, he took a job at a starch plant in New Jersey. Kingsford was convinced that the wheat the company was using would never yield enough starch to make big money. He beseeched his bosses to try maize (aka Indian corn). His colleagues laughed at him.

Kingsford was undeterred. He began doing his own research at home. He borrowed equipment from locals and for years tried everything he could think of to extract starch from corn. One day, long into his efforts, he experimented by mixing corn mush with wood-ash lye. It didn’t work and Kingsford dumped the work in the garbage. He next tried to combine the corn with a solution of lime. Again, he experienced failure. Surely discouraged by this point, he dumped this combination in the same tub and took a break from the whole process.

Sometime later, Kingsford was ready to go at it again. But before setting off in a new direction, he decided to clean up. He picked up the tub from his previous efforts and began emptying it when he noticed something. At the bottom of the garbage was pure, perfectly separated white starch. The unintended combination of the discarded lye and lime with the corn had yielded exactly what he’d been searching for all these years.

In 1842 he went to market with his new starch, which was easier to produce in large quantities than any previous option. At times in Kingsford’s life, he’d taken jobs to support his widowed mother and even initially moved to the United States without his family to make sure he could earn enough money to take care of them. Within less time than it took him to make his discovery, Kingsford was a rich man. In 1848 his new company produced 1.3 million pounds of starch, and by 1859 the annual output was 7 million pounds.

Hot Dog Bun: Small carts and glove thieves

The hot dog is without a doubt the greatest contribution German immigrants have ever made to the American food scene. (Sorry, boosters of stollen or fans of German red cabbage; it’s true.) As one would expect, the frankfurter, a slender smoked cousin of the bratwurst, originated in the German town of Frankfurt centuries before German-Americans began selling them in the United States in the 1800s.

While those sausages were very popular on their own, what turned them into American icons—think baseball, apple pie, and Chevrolet—was the bun, which made the meal an on-the-go favorite from ballparks to boardwalks. (Fun fact: Yale students were among the first to use the term “hot dog” in 1895. Presumably it was because the tube meat reminded them of another German import—the dachshund.)

So where did the hot dog bun come from? Many give that honor to a Coney Island man named Charles Feltman in 1871. According to writer Jeffrey Stanton, Feltman’s customers wanted hot sandwiches, but the New York butcher’s pie cart was too small to pack a variety of options on his rounds. In need of a simple alternative he came up with the idea of turning his slim sausages into sandwiches by using an elongated roll. New York was a hub for hot dogs and along with Feltman, a baker by the name of Ignatz Frischmann, who was a Feltman contemporary, has also been floated as the bun inventor by at least one scholar.

That said the New Yorkers aren’t the only people to stake a claim to the indispensible bun’s marriage to the hot dog. The other main contender provides a far more colorful explanation for the bready addition. Anton Ludwig Feuchtwanger was a German-American vendor in St. Louis, who sold sausages in the days before the hot dog moniker. He called them “red hots,” and in 1883 he recognized the difficulty of eating the tube meat by hand. His solution: providing his customers with white gloves to wear while enjoying his goods. The gloves would keep patrons’ hands clean, help avoid scalding from the sizzling sausag

e, and add a little class to the affair. Solving one problem led to another: a frustrated Feuchtwanger discovered some less scrupulous buyers were walking off with the gloves. He grew weary of the cost of replacing them. So the vendor went to a local baker (some say it was his brother-in-law) and the result was an inexpensive soft bun.

No doubt, Feuchtwanger’s story feels a bit too flavorful. After all, reusing gloves doesn’t sound too hygienic. If he was doing good business, his laundry bills must have been crushing. Nevertheless, many publications have given Feuchtwanger recognition for the invention. The Oxford Companion to Food lists both Feuchtwanger and Feltman as inventors and doesn’t pass judgment on which vendor deserves acclaim. (The book, unlike most who discuss Feuchtwanger, avoids the glove tale.)

Even if he wasn’t the first and his glove story was more marketing myth than reality, Feuchtwanger positively played a role in making the bun a staple in the Midwest. At the 1904 World’s Fair in his hometown of St. Louis, Feuchtwanger was a popular concessionaire who did really well with his hot dog-plus-bun combination. Feuchtwanger’s stand was so popular that years later many erroneously attribute his glove story to that event. Thus, even if Feltman came first, Feuchtwanger and his efforts definitely helped expand the love for sausage on a bun.

Ice-Cream Cone: Debatable world’s fair find

The ice-cream cone’s origin is considered by many to be as muddied as a thick scoop of Rocky Road. Nevertheless, according to the International Ice Cream Association, there is an official tale, which goes like this:

It all took place at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair (aka the Louisiana Purchase Exposition). There had previously been similar events of epic scale, but nothing compared to this Missouri attraction, which inspired the Judy Garland film classic Meet Me in St. Louis. Not only did it host the Olympic Games and attract some twenty million people over a seven-month span, but it was also credited with popularizing, among other edible delights, the ice-cream cone.

Enter Syrian-born Ernest Hamwi. A recent immigrant to the United States, he set up a concession stand at the fair hoping to entice patrons with zalabia, a crisp round waffle-like pastry from his home country. Next to Hamwi’s spot was an ice-cream vendor—one of the fifty or so at the exposition. The seminal moment came on a particularly hot day when Hamwi’s neighbor ran out of bowls and faced a line of customers with no way to provide ice cream. Hamwi stepped in, reshaping his zalabia into a cone. The creation provided customers with a way to enjoy the treat and the day was saved. From then on he named it the “World’s Fair Cornucopia.” It spread to other concessionaires and the rest is history.

The only problem: Not everyone endorses that history. We can confirm Hamwi did establish a cone business, the Missouri Cone Company, in 1910. But food experts have been hard-pressed to corroborate any of his 1904 story. Further complicating the matter is a handful of different vendors from the fair who also take credit. A Norfolk, Virginia, restaurant owner named Albert Doumar has long claimed his uncle Abe was the one to modify a zalabia and come up with the conical confection. He even wrote a dramatically named book about it called The Saga of the Ice Cream Cone.

Then there are two different sets of brothers—Nick and Albert Kabbaz and Charles and Frank Menches. The Kabbazes were Syrian immigrants, who allegedly worked for Hamwi. They supposedly showed their boss how to turn the zalabia into an ice-cream holder. Charles Menches claims he came up with it to impress a lady (in contrast, some assert that the Menches brothers were the ice-cream vendors next door to Hamwi who benefited from his inspiration). The Menches family was an early adopter as they did start their own cone company just one year after the fair. Another claimant was the Turkish-born David Avayou, who said he was inspired by French paper or metal cones.

If all that wasn’t enough, an Italian-American named Italo Marchiony patented his own cone-like ice-cream holder the year before the 1904 fair. Still, some argue that Marchiony’s creation wasn’t really a cone. “He actually patented this mold that made little pastry cups,” according to food author Anne Cooper Funderburg. “They looked like tea cups.” One final contestant: Agnes Bertha Marshall, a British writer who included an entry for “cornets with cream” in an 1888 cookbook (a cornet remains British-speak for an ice-cream cone).

Are you confused yet? So was Dairy Queen when it wanted to celebrate the one hundredth anniversary of the cone and ended up doing it twice—once in 2003 in honor of Marchiony and a second time in 2004 to recognize the impact the St. Louis World’s Fair had on the cone. (Apologies, Agnes—your effort didn’t get props from the ice-cream chain.)

As for who at the fair really deserves credit, it’s a conundrum so great that, on a slow news day in 2004, the Chicago Tribune devoted an editorial to the topic.

“Many of the cone-creation tales involved coming up with something on the spot to hold ice cream,” the newspaper wrote. “So while the paternity of the cone may be unclear, necessity was clearly the mother of this invention. It just may be that more than one fair vendor or patron needed emergency ice cream assistance at the same time in St. Louis 100 years ago.”

In the end, it’s clear the Chicago Tribune, like many, didn’t want to get their hands sticky with this one.

Maple Syrup: Native American domestic clash

Check out any website devoted to maple syrup making and you’re bound to come across the origin story of the Iroquois chief Woksis and his wife Moqua. The legend usually goes as follows: Woksis had thrown his tomahawk into a maple tree one night just before going to bed. The next morning he pulled it out and left to go on a hunt. It was unseasonably warm on this March day and from the tomahawk gash warm maple syrup began trickling down the tree into a pot that happened to be luckily located on the ground below. When it came time for Moqua to fetch water to boil in preparation for dinner, she noticed the liquid in the pot and figured she could save a trip down to the creek. Woksis returned home with some venison, they boiled it up and, eureka, the sweetness of the meal spurred them and other Native Americans to begin cutting into trees to extract the sweet nectar.

Is there any truth to the story?

We are certain many Native American tribes produced maple syrup before the arrival of European settlers. The Algonquin called the maple sugar sinzibukwud (meaning “drawn from wood”) and the Ojibways named it sheesheegummawis (“sap flows fast”). In addition, tomahawks might have been used to cut gashes in maple trees as part of the extraction process. Tribes were known to use sharp instruments, rather than spigots utilized by Westerners, to get the sap out.

As for Woksis and Moqua’s role, the story appears to have gotten its start in modern literature from an 1896 Atlantic Monthly article written by Rowland E. Robinson. His telling of the tale isn’t quite as, well, sweet as the current narrative. Robinson depicts Woksis as a grump who before going off to “the chase” for the day tells his wife to cook up some moose meat. He warns her that if she does a bad job “she might be reminded of the time he stuck a stake in the snow.” (I’m not sure what that means, but it doesn’t sound good.) Moqua promises “strict compliance” and starts melting some snow in a pot for water. She then goes about her business making new moccasins for Woksis. Moqua gets so focused on her work that she doesn’t notice that the frayed bark cord used to hang the pot over the fire is about to break until it’s too late. All the water spills out of the container and Moqua gets nervous and runs outside. There she pulls some sap from a great maple as a water alternative (in this version, the tribe knew about maple juices as a “pleasant drink” but hadn’t figured out its broader uses).

Moqua refills the pot, but becomes aghast when she sees the sap has boiled away and the meat has become dark and shriveled. Now she’s really freaked out remembering that whole stake-snow thing. She bolts from the dwelling just as the huffy Woksis returns. When she doesn’t hear any angry comments from her husband, she returns to find her man in pure syrup heaven. He even goes so far as to break the pot to get the remnants of the treacle.

Marmalade: Stormy oranges

Marmalade has long been a British breakfast staple. Chunks of Seville oranges mixed with sugar to produce what’s known as “chip marmalade” is the traditional spread with toast on cold misty mornings from Edinburgh to London. But the first mass producer of the condiment may have never gotten into the business if not for a fortuitously ill-fated voyage.

Janet Keiller was the wife of a store owner in Dundee, Scotland, in the eighteenth century. One day, her husband came home with an odd purchase: Seville oranges. Unlike the sweet succulent fruits our kids eat during halftime at soccer games, these oranges were tart and would have been a tough sell as a peel-and-eat treat. In fact, they were often used at the time as a souring agent for British sauces. Janet was probably confused at the purchase. Her husband likely explained he was being enterprising. The oranges weren’t bound for Dundee (historians believe they were on their way to Leith for the markets either there or in Edinburgh). But the ship carrying the cargo had been battered by a storm and was forced to take refuge in Dundee’s harbor. Unable to complete its journey, the ship’s captain looked to unload some goods at a cut rate.

How the Hot Dog Found Its Bun

How the Hot Dog Found Its Bun