- Home

- Josh Chetwynd

How the Hot Dog Found Its Bun Page 2

How the Hot Dog Found Its Bun Read online

Page 2

It was 1964 on a Friday night in late October and six friends in Buffalo, New York, got out of a Paul Newman movie (likely The Outrage) and headed over to the Anchor Bar. Their buddy, Dominic Bellissimo, was the son of Anchor owners Frank and Teressa, and, though it was 11:30 p.m., they figured it was a good place to finish off the night. Fellas being fellas, the group wanted two things: food and drink. Whether they boozed is unclear, but the group persisted enough about the grub to force chef Teressa to come up with something.

The problem: It was late and Teressa didn’t really have anything going. Surveying the kitchen, she noticed some small chicken wings. At the time, these trifles really had just one destination in a kitchen—a stock pot to become part of a soup or stew. But Teressa took what she had and broiled (some say deep-fried) the little wings. According to Dominic, his mom used the chicken, in part, because it would have been a shame to consign such lovely wings to a soupy end. She then added some margarine and threw on some Frank’s Original Red Hot Sauce that happened to be in the kitchen. A popular brand in western New York, Frank’s (no connection to Frank Bellissimo) is a combo of “aged cayenne red peppers, vinegar, salt, and garlic.”

Upon seeing the plates of basted wings, one of the buddies, Don Zanghi, asked, “What are these?” Another friend replied: “I don’t know, but we better eat.” Zanghi wasn’t sure how to attack the small-but-meaty morsels. He looked at Anchor owner Frank Bellissimo and said, “Frank, there’s no silverware.” Maybe Frank was a trailblazer—or more likely he was tired and wanted to end the conversation—but his terse answer set sail the how-to etiquette for Buffalo wings. He said, “Keep quiet and use your fingers!”

The dish became the toast of Buffalo and beyond. In 1977 the city proclaimed July 29 Chicken Wing Day. Nineteen years later, a special Frank & Teressa’s Original Anchor Bar Buffalo Chicken Wing Sauce came out. It’s similar to Frank’s Original Red Hot Sauce, but includes margarine, spices, and natural gums in its recipe. There’s even a National Buffalo Wing Festival, complete with a Hall of Flame honoring Buffalo Wing greats. Sure enough, Teressa and Frank were inaugural inductees in 2006. Teressa is so revered that the following year one Buffalo man carved an oak statue in her likeness.

Although Frank and Teressa have long since passed on, the Anchor continues to profit from their creation. In 2009 the bar was selling 2,000 pounds of chicken wings a day.

Caesar Salad: Empty refrigerator

As strange as it might sound, the Caesar salad was a dish born in Mexico. It wasn’t named after Julius Caesar, but after its creator, an Italian immigrant to the United States. The likely source of inspiration: kitchen scraps and leftovers. And, if that wasn’t befuddling enough, the dish was meant to be eaten with the hands rather than with a fork.

Caesar Cardini is most often credited with producing this dish dubbed by Paris’s International Society of Epicures in 1953 as “the greatest recipe to originate from the Americas in fifty years.” Cardini moved to America from Italy’s Lake Maggiore area as a young man. When prohibition hit in 1920, he saw a great opportunity for a new business. While living in San Diego he crossed the border into Mexico and opened up a hotel and restaurant in Tijuana. Down south, guests could sidestep the alcohol ban and have good food with some potent spirits. Hotel Caesar lured not only San Diego socialites but also Hollywood stars. Among those who made the trip to Cardini’s establishment were W. C. Fields, Jean Harlow, and Clark Gable.

Needless to say, during holidays—when people wanted to celebrate with a strong drink—the place was a madhouse. July 4, 1924 was one such day. Miscalculating the amount of food he needed, Cardini found his kitchen short on supplies. The story goes that he improvised with what was left, throwing together romaine lettuce, eggs, garlic, croutons, Parmesan cheese, olive oil, and Worcestershire sauce (and possibly a few other items, including lemon juice). Rather than cutting up the lettuce, Cardini presented the dish as a main course with customers picking up whole leaves of romaine in their hands and eating.

The combination enthralled the glitterati and Caesar’s became a pilgrimage spot for foodies. So much so that none other than Julia Child headed down to Mexico with her family to experience Caesar’s creation. In her book, From Julia Child’s Kitchen, the famed writer and chef talked giddily of the trip. She wrote: “One of my early remembrances of restaurant life was going to Tijuana in 1925 or 1926 with my parents, who were wildly excited that they should finally lunch at Caesar’s Restaurant.” Child recounts Cardini himself mixing the dressing for the salad at her family’s table (an act he typically did for patrons).

Not surprisingly with a dish as wonderful as the Caesar salad, its genesis became a hotly contested claim. The assertion that a cook from Chicago invented it in 1903 is generally disregarded, but a more serious challenge comes from Cardini’s own brother, Alex, a former pilot. According to his son and granddaughter, Alex, who worked with Caesar (and also at his own restaurant), whipped up the salad for some Air Force buddies down from San Diego one morning in 1926 after a rough night. In honor of the flyboys, he called it the Aviator Salad.

In a 1973 interview published in the Canadian Magazine, Alex staked his claim. He said he invented the salad first—an impromptu creation made following a lunch discussion with his partner Paul Maggiora. At the same time, Alex didn’t deny his brother had his own leafy handiwork. “One day, my brother Caesar said to me, ‘Everybody talks about your salad,’ so he made one too,” Alex explained. “Customers used to go to Caesar’s place for Caesar’s salad and to Paul and me for mine.”

Most food historians split the difference, giving Caesar praise for coming up with the basic salad in 1924 and Alex glory for the ever-popular addition of anchovies. I have no ties to either of the Cardini men, but Child’s story of traveling to Tijuana to try an already popular dish in 1925 or 1926 appears to predate Alex’s claim to the dish, giving Caesar some support in this fraternal salad disagreement.

Cheese: Not your average bag

Sometimes when discussing food origins—particularly with items that were accidentally discovered—you have to ask yourself: Who was the brave and/or crazy person who took that initial taste? The first person to take a bite of cheese falls squarely in this category.

We don’t know the name of that bold man or woman, but the valiant sampler was almost certainly a prehistoric herder. Cave paintings indicate animal milking occurred in the Libyan Sahara around or before 5000 BC. Another archeological find suggests similar activity in modern Switzerland in approximately 6000 BC. In later centuries, men shepherding goats, sheep, and cows would often store milk in pouches made from animal stomachs (hey, nothing went to waste back then). One part of these beasts’ bellies, called the abomasum, was full of a substance known as rennet. When the milk sat a little too long in the pouches, the rennet went to work creating chunks, known as curds, along with leftover liquid, aka whey.

I’m sure the coagulated bits didn’t smell good. Yet somebody took a piece—hopefully with some alcohol (alas, there weren’t any good pinot noirs at the time)—and gave it a shot. It wasn’t half bad and people began to recognize that if you drained the liquid and dried out the chunks, it kept quite well and could be stored for later eating. (Geek note: Early history gave us a number of accidental discoveries, including bread and beer; I’m giving cheese the love here because compared with that other fare, scarfing prehistoric fromage was surely a far greater gastronomic leap of faith.)

Salt was an early ingredient used to add flavor. As a result, some historians believe that the first cheeses were similar to the brine-cured feta we might find at a fine grocer today. Egyptian, Greek, and Roman cultures matured the cheese-making process, and by the Middle Ages wedges of the stuff were part of European diets. The great king Charlemagne was said to be a big fan—though it’s unclear if he got hooked after trying early Brie or some Roquefort.

In terms of the art of cheese-making, cultures recognized over time that the abomasum was key in the production of chees

e so pieces of that part of the animal stomach were sliced, salted, and dried. They were then added to milk to create curds. For those who find that process stomach turning, you’ll be happy to know that nowadays genetically engineered bacteria are often set up in vats to produce the necessary curdling agent.

As for the quantity of milk necessary to make cheese, it takes approximately eight pounds of milk to produce one pound of cheese.

Cobb Salad: Celebrity restaurateur

During the golden age of Hollywood, The Brown Derby restaurants were the movie industry’s unofficial canteens. Shirley Temple had her tenth birthday at one. Ronald Reagan chose a Derby for his final meal before shipping off for service during World War II. In an episode of I Love Lucy, Lucille Ball’s character headed to the restaurant’s Hollywood location on a trip to Los Angeles to scope out movie stars because she said it was “their watering hole.” As famed movie director Cecil B. DeMille put it in a 1943 telegram: The Derby was “the most famous restaurant in the world.”

At the center of this starry constellation of celebrities was Bob Cobb. Originally hired in 1926 to run the first Derby, Cobb would go on to own the restaurant’s four star-studded locations throughout L.A. The most famous one, which was just off Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street, helped make that intersection internationally known. Cobb was more than just a restaurateur—he was also a close friend to practically every mover and shaker in town. In 1938 he led a group that included luminaries Bing Crosby, Barbara Stanwyck, Gary Cooper, George Burns, and Walt Disney in bringing a high-level minor league baseball team to Los Angeles. Appropriately, the club was named the Hollywood Stars.

Still, all his rubbing elbows with the superstars didn’t cause Cobb to lose focus on his real job: running restaurants. This was practically a round-the-clock responsibility as, at least in the beginning, The Derby offered twenty-four-hour service.

It was the combination of those long days and Cobb’s influential friends that produced the Cobb Salad. In the late 1920s, Cobb wearily entered the kitchen in the wee hours one night. Cobb was famished but wasn’t too thrilled with his choices. In the early going, The Derby’s menu was pretty limited to such simple dishes as hamburgers, hot dogs, grilled cheese sandwiches, and chili. Cobb wanted something different and pulled out whatever leftovers he could find to avoid the same-old, same-old menu choices. Because he was tired, Cobb went for something that could be prepared simply. He chopped up some lettuce, chicken, and a few other ingredients and started munching.

He was in the midst of his impromptu salad when four Hollywood bigwigs, including studio mogul Jack Warner (of Warner Bros. fame) and Sid Grauman (founder of Hollywood’s Chinese Theatre), checked in on their buddy after seeing a film preview. The men liked the look of Cobb’s meal and asked for their own plates of what was intended to be a one-off concoction.

Those in the know began ordering the off-menu salad almost immediately. But Cobb waited to add it to the menu until he’d perfected his unplanned masterpiece. The final dish featured finely chopped chicken breast, iceberg lettuce, romaine, watercress, chicory, chives, tomatoes, avocados, bacon, hard-boiled eggs, Roquefort cheese, and french dressing. When Cobb opened up the Hollywood Derby in 1929, the Cobb Salad finally became an official menu item. Although The Brown Derby restaurants no longer exist in L.A., the Cobb Salad remains a worldwide star.

Kellogg’s Corn Flakes: Distracted, disagreeable brothers

Will Keith “W. K.” Kellogg had it tough in the early years of his life. He left school after sixth grade and held a number of menial jobs. As a twenty-four-year-old, he dourly wrote in his diary, “I feel kind of blue. . . Am afraid that I will always be a poor man the way things look now.” His older brother, John Harvey, added to his pangs of inferiority. A renowned doctor, John Harvey set up a hospital and health spa called The Battle Creek Sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan, which was the place for many of America’s elite looking to get fit in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Noted guests included Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, J. C. Penney, and President William H. Taft.

W. K. would eventually go to work for his brother, which was a pretty humiliating endeavor. W. K. made a paltry six dollars a week at the Sanitarium, never earning more than eighty-seven dollars a month during his twenty-five years on the job. He apparently wasn’t allowed to go on vacation until he’d worked there for seven years. His responsibilities ranged from balancing the books and running the organization’s mail-order business to shining his brother’s shoes and giving him shaves.

Thankfully for W. K., fate intervened in an unexpected way. A Seventh-day Adventist, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg had religious convictions that required him to focus intently on producing food that was good for the body. At the heart of many of the Sanitarium’s creations were grains. This even included trying to produce a grain alternative to coffee. Among the other efforts was a more digestible substitute for basic bread. It was during this process that W. K. got his big break.

In 1894 the pair was experimenting with boiling wheat dough. During the process they were called away. When they came back, the dough had dried out. Nevertheless, they put the stale stuff through rollers with the hopes it would still be transformed into a long flat sheet of dough. Instead, the result was a bevy of small wheat flakes. The Sanitarium’s patients loved the invention, which they called Granose.

W. K. saw a chance to make his mark. Dr. Kellogg wasn’t as enthused. The doctor wouldn’t even give his brother space for a proper factory to develop the discovery. Still, the resourceful W. K. was able to produce and sell 113,400 pounds of the cereal in 1896. With a little more tinkering, the brothers found replacing wheat with corn as the basis for the flakes offered an even tastier option. Called Sanitas Toasted Corn Flakes, the new cereal continued to do the business.

It was time for W. K. to move out of his brother’s shadow—though he did it with some trepidation. W. K. waited until Dr. Kellogg went on an extended trip to Europe and built a proper factory in 1900. The elder Kellogg wasn’t happy upon his return, insisting that W. K. reimburse him $50,000 in construction costs.

The big rift finally came during another one of Dr. Kellogg’s trips to Europe. (For all his education, the good doctor clearly didn’t realize these trips weren’t such a good idea.) W. K. decided that the only way to expand the market for his corn flakes was to add sugar. For Dr. Kellogg, this was sacrilegious. Sugar was one of the ingredients that served to undermine good health. W. K. insisted and set up his own business, Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company, in 1906. While the pair would remain in business together for some time, squabbling over the product led to lawsuits. In the end the less-educated, but ever scrappy W. K. would win the primary right to use the Kellogg name commercially. By this time W. K. had redubbed his cereal Kellogg’s Corn Flakes in order to differentiate it in a marketplace full of competitors.

Nachos: Ravenous army wives

Picture a group of typical nacho eaters. You’d probably imagine sports-obsessed men at a bar wearing replica jerseys with the names of their favorite players sewn on the back. Of course there would also be a pitcher of beer on the table. Surprisingly, the first people to enjoy this popular cheese-laden tortilla chip appetizer were far from that image. The original plate of nachos was prepared for a group of proper military officers’ wives who were probably more accustomed to a snack of petite sandwiches and tea.

It all happened in 1943 in Piedras Negras, Mexico. The border town was across the Rio Grande River from Eagle Pass, Texas, which during World War II was home to Eagle Pass Army Airfield. For the married women on this US Army Air Force base, crossing the border to shop and enjoy the Mexican culture was a popular diversion.

One day a gaggle of the ladies moseyed over to a Piedras Negras restaurant called the Victory Club. The establishment’s maitre d’—Ignacio “Nacho” Anaya—was there to greet them, but he had a big problem: He couldn’t locate the cook. Not wanting to turn away the patrons, he put on his chef’s hat. He lo

oked around the kitchen and threw together what he had, which according to The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink “consisted of neat canapes of tortilla chips, cheese, and jalapeno peppers.” In a dash of irony, Anaya’s son would tell the San Antonio Express-News in 2002 that the cheese his father used that day was from Wisconsin. He also said that tostados were used to make the first chips. In the years that followed Anaya became the restaurant’s head chef—after all, how could you not give that job to the man who created nachos? The dish took on Anaya’s nickname and was advertised as “Nacho Specials” on both sides of the border.

The combo of chips and melted cheese spread rapidly. By the 1960s it was a popular component of Tex-Mex cuisine. But its place as a global phenomenon owes some tribute to a man named Frank Liberto, who turned nachos into stadium food. In 1977 Liberto unveiled a new nacho concession at Arlington Stadium, home of baseball’s Texas Rangers at the time. Because real cheese didn’t have a great shelf life (and melting it would require an oven or broiler), Liberto devised a fast food form of Anaya’s masterpiece that was part cheese and part secret ingredients. The new sauce didn’t need to be heated and, when it came to shelf life, it could likely survive a nuclear blast. Its formula was so hush hush that a twenty-nine-year-old man was arrested in 1983 for trying to buy trade secrets divulging Liberto’s formula.

When famed Monday Night Football announcer Howard Cosell tasted Liberto’s variation on the nacho theme in 1977, he began talking about it incessantly on air, increasing sales. As for Anaya, his son tried to help him trademark the nacho name years after it became a phenomenon but had no luck. Anaya would go on to run his own restaurant, but he never made big money off his crowd-pleasing creation.

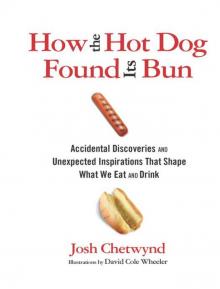

How the Hot Dog Found Its Bun

How the Hot Dog Found Its Bun